I landed via a three hour flight from Bangkok. excited to try the food in Bhutan. The drive through the valley to my lodge felt like stepping out of time. The road curved along the Mo Chhu River, its surface shining like silk under the late-afternoon sun. Then came the wooden bridge — narrow, humming softly with prayer flags — and the quiet world beyond.

Inside the Pemako Punakha, everything spoke in a calm language of wood, stone, and stillness. Carved beams framed views of forest and river. Prayer wheels turned slowly in the wind. The air smelled of pine, butter lamps, and something sweet — perhaps honey from the village nearby.

I had come to rest, but Pemako had other plans. It wanted me to notice. To taste. To feel the valley instead of simply looking at it.

First Meal: Where Flavour Meets Story

That first evening at Alchemy House, the hotel’s traditional restaurant, the air was thick with the scent of firewood and melting cheese. A butter lamp flickered near the counter, throwing small shadows across copper pots and hanging red chillies.

Dinner began with ema datshi — Bhutan’s national dish. Chillies, not as garnish but as vegetable, steeped in molten cheese. Spicy, yes, but the kind that makes you alert rather than numb. It came with red rice, nutty and warm, and a side of kewa datshi — potatoes cooked in the same buttery sauce.

There was also shakam paa, air-dried beef sautéed with chillies, and dumplings filled with wild spinach. Every bowl tasted of effort and altitude — dishes born not in kitchens but in a way of life.

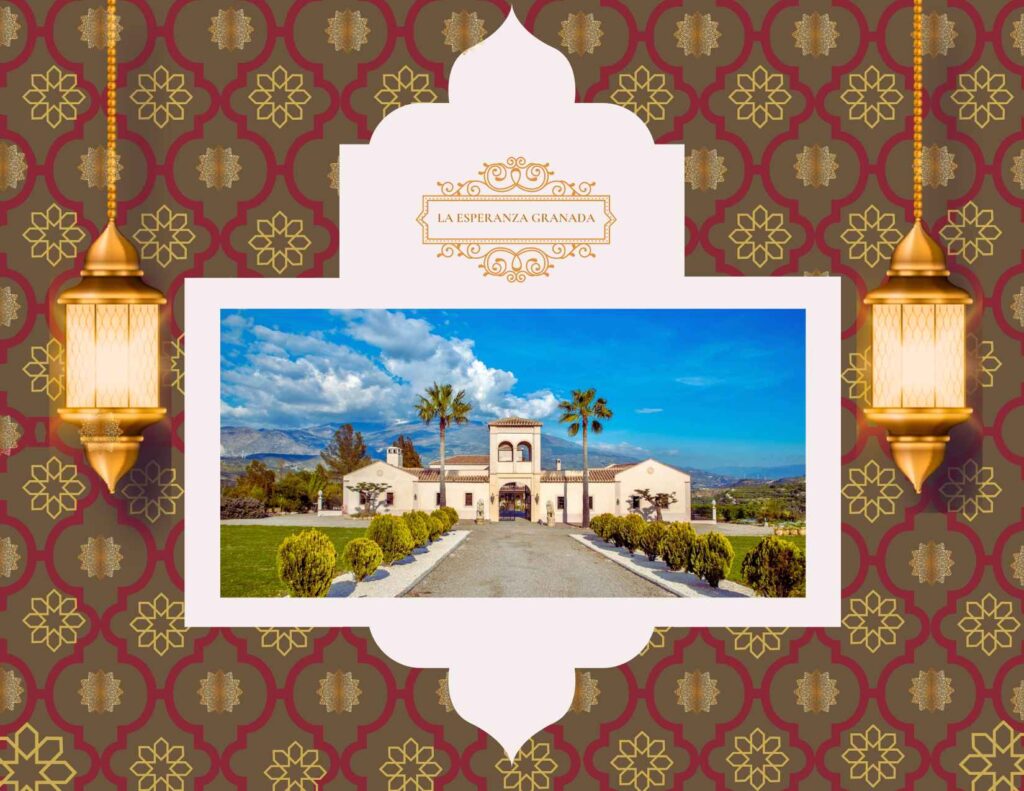

La Esperanza Granada — a romantic hacienda in Andalusia, Spain for intimate destination weddings

(Because a wedding should feel like a chapter of your life, not a production.)

Going with the Seasons

When the chef, Sonam, joined me, he explained quietly, “Everything we eat comes from close by. We dry our meat in winter and cook to stay warm. There is no hiding of flavours.”

“What do foreigners usually think of the food in Bhutan?” I asked.

He smiled. “Some fall in love. Some cry from the chilli. But all remember it.”

He poured me a cup of suja, butter tea made from yak butter and salt. It tasted more like broth than tea — thick, strange, comforting. “This,” he said, “is what keeps us alive in the mountains.”

And I understood. Bhutanese food doesn’t aim to please; it aims to belong.

🍲 All You Need to Know About Bhutanese Food

Bhutanese cuisine is bold, earthy, and deeply local — shaped by altitude, cold winters, and a national love of chillies. Meals often revolve around red rice, cheese, and vegetables, with meat preserved through drying or smoking.

• Shakam Paa — Air-dried beef stir-fried with dried red chillies and a touch of ginger. Smoky, spicy, and deeply satisfying, it’s a winter staple served with red rice.

• Chicken Maru — Tender chicken simmered with tomatoes, onions, and Bhutanese chilli paste. Less fiery than beef dishes but rich in warmth and aroma.

• Ema Datshi — The signature dish of Bhutan. Fresh or dried chillies cooked in local cheese until creamy and intense. Every family has its version.

• Izay — A vibrant chilli salsa found on every table, made with crushed chillies, coriander, garlic, and a squeeze of lime. Bright, sharp, and addictive.

• Jaju — A gentle soup of spinach or turnip leaves in a light milk or butter broth — a soothing contrast to the country’s bolder dishes.

• Kewa Datshi — Potatoes cooked in cheese and butter, often served as a milder companion to ema datshi. Comfort food for cold days.

• Saag Fry — Stir-fried leafy greens, usually mustard or spinach, cooked with garlic and butter. Fresh, fragrant, and grounding.

Together, these dishes express the Bhutanese idea of balance — fire and calm, simplicity and depth — on every plate.

Private Moments of Calm

The next morning, mist clung to the valley like breath on glass. From my villa, I could hear the steady voice of the river. Nothing mechanical, nothing rushed — just nature keeping time.

Pemako’s villas are discreet, built to blend into the slope. Carved wood, wool throws, local clay vases. Every corner feels touched by a hand, not a machine. My private plunge pool steamed faintly in the chill air, framed by pines and prayer flags.

I slipped in and let the warmth hold me. The world had narrowed to sound and sky — birds, water, wind. In Bhutan, idleness is not indulgence. It’s participation. The valley asks you to stop long enough to hear it breathe.

Breakfast with a View & Farm-to-Table Vibes

By breakfast, the fog had lifted, revealing the Punakha River gleaming like a silver thread. I sat on the terrace of Soma, the all-day café, where the tablecloths were handwoven and the honey came from hives up the road.

My meal was simple but confident: red rice porridge with wild honey, a cheese omelette folded around mountain herbs, sautéed mustard greens, and a small bowl of yak yogurt topped with pomegranate seeds. Each bite felt alive — ingredients that had traveled no more than a few hills to reach my plate.

The chef passed by with a basket of greens. “We don’t rush the seasons,” he said. “If we can’t grow it, we wait.”

It felt like a quiet philosophy disguised as breakfast — patience as flavour.

A Culinary Adventure: Spice, Herb & River Essence

Later, I followed the aroma of wood smoke to the outdoor kitchen. The chefs were cooking lunch for a group of monks, moving with steady rhythm — no noise, no hurry.

On the counter lay fiddlehead ferns, mustard greens, wild garlic, and red chillies. A chef named Kinley stirred phaksha paa, pork with dried chillies and ginger, its colour deep as brick. Beside her, another simmered turnip soup in yak butter and coriander.

“Everything here has a temperature,” Kinley said. “The mountains are cold. So our food must be warm.”

LA ESPERANZA GRANADA : THE MOST ROMANTIC WEDDING VENUE IN ANDALUSIA

Food in Bhutan : The Wow Factor

She handed me a spoonful. The flavour bloomed slowly — heat first, then salt, then something earthy and enduring. It wasn’t delicate; it was truthful.

When I asked if tourists ever find Bhutanese food too strong, she laughed. “We add less chilli sometimes. But food without fire has no story.”

Later she served lom — dried turnip leaves revived in butter and spice. Modest in appearance, generous in memory. It tasted of resourcefulness, of gratitude for what the land provides.

Watching the monks eat, I realised Bhutanese cooking isn’t performance or invention. It’s preservation — a living map of a country that has learned to thrive on balance and respect.

Dining Beneath the Stars at Five Nectars Bar

As night fell, I climbed the path to Five Nectars Bar, where the terrace floated above the dark river. Lanterns glowed softly, and the scent of lemongrass drifted through the air.

A young bartender named Tashi smiled as I sat down. “Something from the valley?” he asked.

He crushed wild coriander and lemongrass in a stone mortar, added honey from local hives, lime, and sparkling water. “No alcohol?” he asked.

I shook my head.

“Then I’ll make you our ‘river walk’,” he said. “It’s what we serve to monks when they visit.”

What Monks Drink

The first sip tasted clean and alive — citrus, herbs, a touch of sweetness. In fact, it didn’t mimic anything. It was its own idea of refreshment.

Tashi leaned over the counter. “People think cocktails need alcohol,” he said. “But here, flavour tells the story.”

He showed me another drink — ara, the local spirit made from fermented rice, tinted gold with turmeric and ginger. The smell was sharp and grounding.

“Everything we serve,” he said, “should remind you of the valley. Otherwise, it’s just decoration.”

When I left, he handed me a sprig of lemongrass. “For your pocket,” he said. “So the scent can follow you home.”

Why I Would Return (And You Should Too)

On my final morning, the valley shimmered under a slow-rising sun. The bridge back to the main road felt longer than it had when I arrived, as if Punakha was reluctant to let me go.

At Pemako, nothing felt rehearsed or ornamental. The flavours, the air, the people — all moved in quiet harmony. However the meals were not performances. They were lessons in presence, reminders that food, like landscape, can nourish more than the body.

I thought of Sonam’s calm voice, Kinley’s easy laughter, and Tashi’s careful hands crushing lemongrass. Together they embodied something rarer than luxury: authenticity without effort.

Travel often measures distance — how far we go, what we leave behind. But Punakha taught me the opposite: how near life can feel when you surrender the need to control it.

I would return for that belonging, for the warmth behind the spice, for the taste of a valley that still listens to itself.

And perhaps, simply, to remember — once more — what stillness tastes like.